The Mean Value Theorem

This post describes the mean value theorem and several other theorems of real analysis.

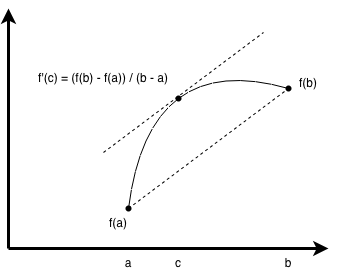

The mean value theorem is a basic, but important, theorem of calculus. Geometrically, it states, roughly speaking, that, given an arc through two endpoints, there exists a point on the arc at which the tangent line is parallel to the secant line through the endpoints, as in the following figure.

Arithmetically it states, roughly speaking, that, given a function \(f\) differentiable on some interval \((a, b)\), there exists a point \(c \in (a, b)\) such that \(f'(c)\) is the mean of the endpoints \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\) on this interval, i.e.,

\[f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}.\]

Intuitively, the tangent line starting a \(f(a)\) must finally "rotate" and become parallel to the secant line at some point before finally ending at the tangent line at \(f(b)\).

Rolle's Theorem

Before stating and proving the mean value theorem, it is useful to state and prove Rolle's theorem, which can be understood as a special case of the mean value theorem.

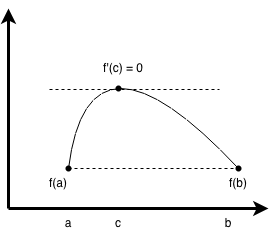

Geometrically, it states, roughly speaking, that, given an arc through two horizontally parallel endpoints (i.e., \(f(a) = f(b)\)), there exists a point on the arc at which the tangent line is horizontal (i.e., its slope is \(0\)), as in the following figure.

Arithmetically it states, roughly speaking, that, give a function \(f\) differentiable on some interval \((a,b)\), there exists a point \(c \in (a,b)\) such that \(f'(c) = 0\).

If we think of the function as modeling the vertical position at a given time of a ball thrown into the air, then the derivative indicates the vertical velocity; at some point, the velocity must transition from positive (going up) to negative (going down) and hence must become zero at some point.

We will prove Rolle's theorem via several other theorems:

- We will establish the boundedness theorem, which states that if \(f\) is continuous on \([a,b]\), then \(f\) is bounded on \([a, b]\).

- Then, using the boundedness theorem, we will establish the extreme value theorem, which indicates that, if \(f\) is continuous on \([a,b]\), then the extrema (maximum and minimum) of \(f\) occur in \([a, b]\).

- Then we will prove the interior extremum theorem (also called Fermat's theorem), which indicates that \(f'(c) = 0\) at any extremum \(c\) interior to an open interval \((a,b)\) whenever \(f\) is differentiable at \(c\).

We can prove Rolle's theorem by putting all of these theorems together.

Boundedness Theorem

We will prove the boundedness theorem by iterative bisection (i.e., by diving the interval into smaller subintervals). We will proceed by contradiction.

First, we require two additional theorems:

- The nested interval theorem indicates that a sequence of nested closed intervals converges to a single point (under appropriate conditions).

- The monotone convergence theorem indicates that a bounded monotone sequence has a limit.

Theorem (Monotone Convergence Theorem). Every bounded monotone sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) has a limit in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Proof. Suppose \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded and monotone.

Case 1. If \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is non-decreasing, define \(L = \sup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n\). By definition, for all \(n\), \(a_n \leq L\) and thus \(0 \leq L - a_n\). Suppose \(\varepsilon > 0\). There exists an \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(L - a_N < \varepsilon\), since if \(L - a_N \ge \varepsilon\) for all \(N \in \mathbb{N}\), then \(a_{N} \le L - \varepsilon\), which means that \(L - \varepsilon\) would be a lesser bound than \(L = \sup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n\), which is a contradiction. For all \(n \ge N\), since \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is non-decreasing, it follows that \(a_N \leq a_n \leq L\). It thus follows that

\begin{align*}0 \leq L - a_n \leq L - a_N < \varepsilon\end{align*}

and hence

\[\lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n = L = \sup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n.\]

Case 2. If \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is non-increasing, define \(L = \inf_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n\) and a similar argument applies. Alternatively, apply the first case with the negation of the sequence \((-a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\). \(\square\)

Theorem (Nested Intervals Theorem). For any nested sequence \(([a_n,b_n])_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) of closed intervals \([a_n, b_n] \subset \mathbb{R}\) (i.e., \([a_{n+1},b_{n+1}] \subseteq [a_n, b_n]\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\)), if \(\lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}(b_n - a_n) = 0\), then the intersection of all the intervals is a single point \(p\), i.e.,

\[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}[a_n, b_n] = p.\]

Proof. First note that the sequence \((a_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded and non-decreasing and hence, by the monotone convergence theorem, has a limit \(A = \lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n = \sup_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n\). Likewise, the sequence \((b_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) is bounded and non-increasing and hence, by the monotone convergence theorem, has a limit \(B = \lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}b_n = \inf_{n \in \mathbb{N}}b_n\). Since \(A\) is a supremum and \(a_n \leq b_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), it follows that \(A \leq b_n\) (since otherwise one of the values \(b_n\) would be the supremum). Since \(B\) is an infimum and \(A \leq b_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), \(A \leq B\). Thus, the interval \([A, B]\) is non-empty. Since \(a_n \leq A \leq B \leq b_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), it follows that

\[[A, B] \subseteq \bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}[a_n, b_n].\]

Now, if \(c \not \in [A, B]\), say, if \(c \lt A\), then, since \(A\) is the supremum, there exists an \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(c \lt a_n\) (since otherwise it would be the case that \(c \ge a_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) and hence \(c\) would be a lesser supremum). Thus, \(c \not \in [a_n, b_n]\) and hence \(c \not \in \cap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}[a_n, b_n]\). It thus follows that

\[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}[a_n, b_n] \subseteq [A, B].\]

and hence

\[\bigcap_{n \in \mathbb{N}}[a_n, b_n] = [A, B].\]

A similar argument applies whenever \(c \gt B\). Finally, note that

\begin{align*}A - B &= \lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}a_n - \lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}b_n\\&=\lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}(b_n - a_n) = 0\end{align*}

and thus \(A = B\). The interval \([A,B]\) is thus degenerate and consists of a single point \(p = A = B\). \(\square\)

Theorem (Boundedness Theorem). If \(f : [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is continuous, then \(f\) is bounded.

Proof. We will proceed by contradiction. Suppose that \(f\) is unbounded on \([a, b]\). Define a nested sequence of closed intervals as follows:

- \([a_0,b_0] = [a, b]\),

- \([a_{n+1},b_{n+1}] = \begin{cases}[a_n, \frac{b_n - a_n}{2}] & \text{if \(f\) is unbounded on \([a_n, \frac{b_n - a_n}{2}]\)} \\ [\frac{b_n - a_n}{2}, b_n] & \text{if \(f\) is unbounded on \([\frac{b_n - a_n}{2}, b_n]\)}\end{cases}\).

This sequence is well-defined since each interval must be bounded on at least one of its respective sub-intervals. By construction, \(b_n - a_n = (b - a) / 2^n\) and thus \(\lim_{n \in \mathbb{N}}(b_n - a_n) = 0\). Thus, by the nested intervals theorem, these intervals intersect in a single point \(p \in [a, b]\). Since \(f\) is continuous, by definition, for any \(\varepsilon > 0\) there exists a \(\delta > 0\) such that \(\lvert f(x) - f(p) \rvert \lt \varepsilon\) whenever \(\lvert x - p \rvert \lt \delta\) and hence \(\lvert f(x) \rvert \lt \lvert f(p) \rvert + \varepsilon\). This means that \(f\) is bounded on the interval \((p - \delta, p + \delta)\). However, \([a_n, b_n] \subseteq (p - \delta, p + \delta)\) whenever \((b-a)/2^n < \delta\), so \(f\) is bounded on \([a_n,b_n]\), which is a contradiction since, by construction, \([a_n, b_n]\) is unbounded. Thus, \(f\) is bounded on \([a, b]\). \(\square\)

Extreme Value Theorem

Next we will prove the extreme value theorem.

Theorem (Extreme Value Theorem). If \(f : [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is continuous, then there exist values \(c, d \in [a, b]\) such that, for all \(x \in [a, b]\), \(f(c) \le f(x) \le f(d)\).

Proof. Since \(f\) is continuous, by the boundedness theorem, \(f\) is bounded on \([a, b]\). By the completeness of the real numbers, since the codomain of \(f\) is a bounded set of real numbers, it therefore has a least upper bound \(M\). We proceed by contradiction. Suppose there is no \(d \in [a, b]\) such that \(f(d) = M\). Then \(f(x) < M\) and thus \(M - f(x) > 0\) for all \(x \in [a, b]\). Since \(M - f(x) > 0\), the following function is defined and continuous on \([a, b]\):

\[g(x) = \frac{1}{M - f(x)}.\]

By the boundedness theorem, \(g\) is bounded, and hence there exists some \(N > 0\) such that \(g(x) \le N\) for all \(x \in [a, b]\), i.e.,

\[\frac{1}{M - f(x)} \le N.\]

Since \(M - f(x)\) is positive and \(N\) is positive, it follows that

\[f(x) \le M - \frac{1}{N}.\]

However, this implies that \(M - (1/N)\) is a lesser upper bound that \(M\), which was supposed to be the least upper bound, which is a contradiction. Therefore, there exists a \(d \in [a, b]\) such that \(f(d) = M\). \(\square\)

Interior Extremum Theorem

Next we will establish the interior extremum theorem (also called Fermat's theorem).

Theorem (Interior Extremum Theorem). For any function \(f : (a,b) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), if \(f\) is differentiable at a point \(x_0 \in (a,b)\) and \(f\) attains a local extremum at \(x_0\), then \(f'(x_0) = 0\).

Proof. Suppose that \(f\) attains a local maximum at \(x_0\). Then there is a neighborhood of \(x_0\) on which \(f(x_0) \ge f(x)\) for all \(x\) within this neighborhood. Thus, whenever \(x \gt x_0\) in this neighborhood,

\[\frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0} \le 0,\]

and, since \(f\) is differentiable,

\[f'(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0^+}\frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0} \le 0.\]

Likewise, whenever \(x \lt x_0\) in this neighborhood,

\[\frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0} \ge 0,\]

and, since \(f\) is differentiable,

\[f'(x_0) = \lim_{x \to x_0^-}\frac{f(x) - f(x_0)}{x - x_0} \ge 0.\]

Thus \(0 \le f'(x_0) \le 0\), so \(f'(x_0) = 0\). A similar argument applies if \(f\) attains a local minimum at \(x_0\). \(\square\)

Proof of Rolle's Theorem

Now we are prepared to prove Rolle's theorem.

Theorem (Rolle's Theorem). If a function \(f : [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is continuous on a closed proper interval \([a, b]\), differentiable on the open interval \((a, b)\), and \(f(a) = f(b)\), then there exists at least one point \(c \in (a, b)\) such that \(f'(c) = 0\).

Proof. We proceed by cases. Let \(k = f(a) = f(b)\).

Case 1. Suppose \(f\) is constant, i.e.,\(f(x) = k\) for all \(x \in [a, b]\). Then \(f'(x) = 0\) for all \(x \in [a, b]\).

Case 2. Suppose that \(f(x) \gt k\) for some \(x \in [a, b]\). By the extreme value theorem, the maximum value \(f(d)\) occurs at some point \(d \in [a, b]\), and, since \(f(d) \ge f(x) \gt k\), it follows that \(f(d) \gt k\) and thus \(d \ne a\) and \(d \ne b\), so \(d \in (a, b)\). By the interior extremum theorem, \(f'(d) = 0\).

Case 3. Similar to case 2, except with the minimum. \(\square\)

Proof of the Mean Value Theorem

Now we are finally prepared to prove the mean value theorem.

Theorem (Mean Value Theorem). For any continuous function \(f : [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), if \(f\) is differentiable on the proper interval \((a, b)\), then there exists some \(c \in (a, b)\) such that

\[f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}.\]

Proof. Consider the following function:

\[g(x) = f(x) - x \cdot \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}.\]

Note that this function is continuous and that \(g(a) = g(b)\). Thus, by Rolle's theorem, it follows that there exists a point \(c \in (a, b)\) such that \(g'(c) = 0\), and hence

\[g'(c) = f'(c) - \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} = 0,\]

which means that

\[f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} = 0.\]

\(\square\)